Quotes Incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note

A Deed of Dreadful Note is a piece of historical fiction, created by blending The Leavenworth Case with Anna’s personal history, recorded thoughts, and relationships since, as she said herself, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Where possible, I have used Anna’s own words to capture the grace and wit with which she approached the world and her writing, in particular.

I’ve now collected all of the quotes incorporated into the novel in one easy-to-access place. You’ll want to bookmark this for your Book Club gathering later!

Quotes Used in A Deed of Dreadful Note

Chapter Epigraphs

“A deed of dreadful note.” —Shakespeare, Macbeth (quoted as an epigraph before the opening chapter of The Leavenworth Case by Anna Katharine Green)

“I have found that the incidents in books which people pick out as improbable are the very ones which are founded on fact. Truth is stranger than fiction.” —Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “I never write a single story unless I am in the mood for it. I can not. I have to feel and live the parts.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “Life’s Facts as Startling as Fiction,” by Ruth Snyder

- “For, as you know, dead men tell no tales.” —Gryce, The Leavenworth Case, 1878

- “…a confusion too genuine to be dissembled and too transparent to be misunderstood.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “Any attempt at consolation on the part of a stranger must seem at a time like this the most bitter of mockeries; but do try and consider that circumstantial evidence is not always absolute proof.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “[Anna Katharine Green is] ‘the foremost representative in America today of police-court literature’; yet to us this reference seems unsatisfactory, inadequate. It conveys no hint of the constructive skill, the imaginative power and the perceptive faculties necessary for the praiseworthy writing of police-court literature; and, furthermore, it offers no suggestion of Anna Katharine Green’s exquisite sense of humor.” — E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901

- “The hand will often reveal more than the countenance…”—The Leavenworth Case, 1878

- “At this critical time her father was friend and counsellor.… When doubts arose, when discouragement appeared, he was nearby to cheer her and to advise. He enlisted her sympathy in different cases that interested him; he sharpened her wits ; he discoursed to her on his own interesting experiences; he contributed judicious criticisms; above all, he fostered her confidence in her own powers.” — E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901

- “All animated and glowing with his enthusiasm, he eyed the chandelier above him as if it were the embodiment of his own sagacity.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “I own that I was surprised at the softening which had taken place in her haughty beauty.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “I even detected Mr. Gryce softening towards the inkstand.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “My imagination may be stirred by some detail or situation, but until I am thoroughly acquainted with my people, their environment, the thoughts they think, the glances they give, in fact every little element that goes to make up their relationship to the drama in which they are cast, I sit and think, feel and dream, but do not write.”—Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

- “I cannot but feel a desire to write him a play in which he may have an opportunity to show himself in a part equally strong but more sympathetic. Whether or not this will eventuate in anything has not yet been communicated to me by the muse.’” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, by T. Fisher Unwin, 1895

- “The greatest mistake a girl can make is to marry in haste… they do not study his instincts and ideals. They do not know the character of the man they intend to marry.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “Life’s Facts as Startling as Fiction,” by Ruth Snyder

- “The other night I had a wonderful dream, which has impressed a story on my mind.… It is so passionate, so strong, so subtle, so dread, dark, and heart-rending, it ought to be written with fire and blood.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

- “Her father was a well-known lawyer; indeed, the Greens, we have been told, were a family of lawyers. This may account for the skill with which the daughter has tied and cut Gordian knots. It unquestionably accounts for her nimble imagination, her skill in producing subtle hypotheses and her strength in handling the most intricate psychological problems.” —E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston, “Anna Katharine Green,” Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901

- “Character added to loveliness gives us those rare specimens of womanly perfection which assure us that poetry and art are not solely in the minds of men.” —Anna Katharine Green, “Is Beauty a Blessing?” The Ladies’ Home Journal, 1891

- “She does not write unless vitally interested in her characters and plot.”— “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895

- “It will require all my enthusiasm, study and power, and then I may fall short, but I believe I shall sometime try. Perhaps it is somewhat sensational, but I hope by characterization and earnestness to lift it to a higher ground.” —Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

- “You expected revelations, whispered hopes, and all manner of sweet confidences; and you see, instead, a cold, bitter woman, who for the first time in your presence feels inclined to be reserved and uncommunicative.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “It will be observed that she does all that is necessary to cultivate an air of authenticity in what she writes.”—T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895

- “With her, action speaks louder than words.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895

- “They thought me a good machine and nothing more.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “I endeavored to put away all further consideration of the affair till I had acquired more facts upon which to base the theory.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “But, as is very apt to be the case in an affair like this, love and admiration soon got the better of worldly wisdom.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “All is closely related, no word is written that has not its specific use in the makeup of my work. I proceed as one might to solve some abstruse problem, by clearly defined lines and deliberately planned steps.”—Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau,” by Mary R. P. Hatch

- “The chain was complete; the links were fastened; but one link was of a different size and material from the rest; and in this argued a break in the chain.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “Her circumstances, moreover, though stranger than fiction, are not stranger than truth.” —T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895

- “Her books are read and re-read, and with keener zest upon the subsequent reading than upon the first, when her remarkable constructive skill does not stand in the way of appreciating the many touches indicative of a truly comprehensive and artistic mind.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895

- “I did not consult my knowledge, sir, in regard to the subject: only my feelings.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “I declare, now that the thing is worked up, I begin to feel almost sorry we have succeeded so well.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “A web seemed tangled about my feet.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “Few authors wait to have a story to tell.” — “Anna Katharine Green and Her Work,” Current Literature, 1895

- “Now it is a principle which every detective recognizes, that if of a hundred leading circumstances connected with a crime, ninety-nine of these are acts pointing to the suspected party with unerring certainty, but the hundredth equally important act one which that person could not have performed, the whole fabric of suspicion is destroyed.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “Her criminals are creatures of circumstance rather than hard-hearted wretches. They have an air of relief at being tracked down—a sure sign of a redeeming flaw in their devilry.” —T. Fisher Unwin, Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, 1895

- “I will not lose body and soul for nothing.”—The Leavenworth Case

- “And leaving them there, with the light of growing hope and confidence on their faces, we went out again into the night…”—The Leavenworth Case

“‘Have I read The Leavenworth Case? I have read it through at one sitting.… Her powers of invention are so remarkable—she has so much imagination and so much belief (a most important qualification for our art) in what she writes, that I have nothing to report of myself, so far, but most sincere admiration.… Dozens of times in reading the story I have stopped to admire the fertility of invention, the delicate treatment of incidents—and the fine perception of the influence of events on the personages of the story.” —Letter from Wilkie Collins to George Putnam, reprinted in The Critic

“A.K. Green Dies. Noted Author, 88. ‘The Leavenworth Case’ in ’78 Followed by 36 Other Books. Wife of Charles Rohlfs. Wanted to Write Poetry. Wrote Detective Stories to Draw Attention to Her Verse. Changed Mystery Fiction.” —New York Times, April 12, 1935

Poetry by Anna, published in The Defense of the Bride, and Other Poems (1882), written prior to The Leavenworth Case

- Through the Trees

If I had known whose face I’d see

Above the hedge, beside the rose;

If I had known whose voice I’d hear

Make music where the wind-flower blows, —

I had not come; I had not come.

If I had known his deep ‘I love.’

Could make her face so fair to see;

If I had known her shy ‘And!’

Could make him stoop so tenderly, —

I had not come: I had not come.

But what knew I? The summer breeze

Stopped not to cry ‘Beware! beware!’

The vine-wreaths drooping from the trees

Caught not my sleeve with soft ‘Take care!’

And so I came, and so I came.

The roses that his hands have plucked,

Are sweet to me, are death to me;

Between them, as through living flames

I pass, I clutch them, crush them, see!

The bloom for her, the thorn for me.

The brooks leap up with many a song —

I once could sing, like them could sing;

They fall; ’tis like a sigh among

A world of joy and blossoming. —

Why did I come? Why did I come?

The blue sky burns like altar fires —

How sweet her eyes beneath her hair!

The green earth lights its fragrant pyres;

The wild birds rise and flush the air;

God looks and smiles, earth is so fair.

But ah! ‘twixt me and you bright heaven

Two bended heads pass darkling by;

And loud above the bird and brook

I hear a low ‘I love,’ ‘And I—’

And hide my face. Ah God! Why? Why?

- Pearls

The wave that floods the trembling shore,

And desolates the strand,

In ebbing leaves, ‘mid froth and wreck,

A shell upon the sand.

So troubles oft o’erwhelm the soul;

And shake the constant mind,

That in retreating leave a pearl

Of memory behind.

- At the Piano

Play on! Play on! As softly glides

The low refrain, I seem, I seem

To float, to float on golden tides,

By sunlit isles, where life and dream

Are one, are one; and hope and bliss

Move hand in hand, and thrilling, kiss

‘Neath bowery blooms,

In twilight glooms,

And love is life, and life is love.

Play on! Play on! As higher rise

The lifted strains, I seem, I seem

To mount, to mount through roseate skies,

Through drifted cloud and golden gleam,

To realms, to realms of thought and fire,

Where angels walk and souls aspire,

And sorrow comes but as the night

That brings a star for our delight.

Play on! Play on! The spirit fails,

The star grows dim, the glory pales,

The depths are roused — the depths, and oh!

The heart that wakes, the hopes that glow!

The depths are roused: their billows call

The soul from heights to slip and fall;

To slip and fall and faint and be

Made part of their immensity;

To slip from Heaven; to fall and find

In love the only perfect mind;

To slip and fall and faint and be

Lost, drowned within this melody, —

As life is lost and thought in thee.

Ah, sweet, art thou the star, the star

That draws my soul afar, afar?

Thy voice the silvery tide on which

I float to islands rare and rich?

Thy love the ocean, deep and strong,

In which my hopes and being long

To sink and faint and fail away?

I cannot know. I cannot say.

But play, play on.

- Shadows

A zephyr stirs the maple trees,

And straightway o’er the grass

The shadows of their branches shift;

Shift, Love, but do not pass.

So, though with time a change may come

Within my steadfast heart,

The shadow of thy form may stir,

But can not, Love, depart.

Quotes from The Leavenworth Case, 1878, incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note (not including the times I point out what she’s written in The Leavenworth Case)

- Gryce: “Eagerness is not a fault; only the betrayal of it.”

- Gryce: “It is not enough to look for evidence where you expect to find it. You must sometimes search for it where you don’t.”

- [paraphrased]

“There are seven chambers here, and they are all loaded.”

A murmur of disappointment followed this assertion.

“But,” he quietly said after a momentary examination of the face of the cylinder, “they have not all been loaded long. A bullet has been recently shot from one of these chambers.”

“How do you know?” cried one of the jury.

“How do I know? Sir,” he said, turning to the coroner, “will you be so kind enough to examine the condition of this pistol?” And he handed it over to that gentleman. “Look first at the barrel; it is clean and bright, you will say, and shows no evidence of a bullet having passed out of it very lately; that is because it has been cleaned. But now, observe the face of the cylinder: what do you see there?”

“I see a faint line of smut near one of the chambers.”

“Just so; show it to the gentlemen.”

It was immediately handed down.

“That faint line of smut, on the edge of one of the chambers, is the telltale, sirs. A bullet passing out always leaves smut behind. The man who fired this remembered the fact, cleaned the barrel, but forgot the cylinder.”

- Gryce: “Everyone and nobody. It is not for me to suspect, but to detect.”

- Quote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “And often-times, to win us to our harm, the instruments of darkness tell us truths, win us with honest trifles, to betray us in deepest consequence

- Quote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “A deed of dreadful note.”

- Quote from Macbeth used as epigraph in Leavenworth Case: “When our actions do not, our fears do make us traitors.”

- Gryce: “A servant maid who has a grievance is a very valuable assistant to a detective.”

- Gryce: “I have had a communication from London in regard to the matter. I’ve a friend there in my own line of business, who sometimes assists me with a bit of information, when requested. It is enough for me to telegraph him the name of a person, for him to understand that I want to know everything he can gather in a reasonable length of time about that person.” “And you sent the name of Mr. Quinn to him?” “Yes, in cipher.”

- Gryce: “Oh, you know I have no opinion. I gave up everything of that kind when I put the affair into your hands.”

- Gryce: “May I ask, whether you expect to work entirely by yourself; or whether, if a suitable coadjutor were provided, you would disdain his assistance and slight his advice?”

- Gryce: “Not but that a word from you now and then would be welcome. I am not an egotist. I am open to suggestions: as, for instance, now, if you could conveniently inform me of all you have yourself seen and heard in regard to this matter, I should be most happy to listen.”

- “He has given me a possible clue——” “Wait,” said Mr. Gryce; “does he know this? Was it done intentionally and with sinister motive, or unconsciously and in plain good faith?” “In good faith, I should say.” Mr. Gryce remained silent for a moment. “It is very unfortunate you cannot explain yourself a little more definitely,” he said at last. “I am almost afraid to trust you to make investigations, as you call them, on your own hook. You are not used to the business, and will lose time, to say nothing of running upon false scents, and using up your strength on unprofitable details.”

- Gryce: “In other words, you are to play the hound, and I the mole; just so, I know what belongs to a gentleman.”

- Gryce: “he was engaged in holding a close and confidential confab with his fingertips, and did not appear to notice”

- Harwell description: “The man lacked any distinctive quality of face or form agreeable or otherwise—being what one might call in appearance a negative sort of person, his pale, regular features, dark, well-smoothed hair and simple whiskers, all belonging to a recognized type and very commonplace. Indeed, there was nothing remarkable about the man, any more than there is about a thousand others you meet every day on Broadway.”

- “Taking a piece of paper, she jotted down the leading causes of suspicion against Eleanore as follows”

- Gryce: “Did you ever know a woman who cleaned a pistol? No. They can fire them, and do; but after firing them, they do not clean them.”

- “A flush of lovely color burst upon us. Blue curtains, blue carpets, blue walls. It was like a glimpse of heavenly azure in a spot where only darkness and gloom were to be expected. Fascinated by the sight, I stepped impetuously forward, but instantly paused again, overcome and impressed by the exquisite picture I saw before me.”

- “I am very much astonished,” Mr. Gryce went on, winking at me in a slow, diabolical way which in another mood would have aroused my fiercest anger.

- “Judging from common experience, we had every reason to fear that an immediate stop would be put to all proceedings on our part, as soon as the coroner was introduced upon the scene. But happily for us and the interest at stake, Dr. Fink, of R ——, proved to be a very sensible man. He had only to hear a true story of the affair to recognize at once its importance and the necessity of the most cautious action in the matter. Further, by a sort of sympathy with Mr. Gryce, all the more remarkable that he had never seen him before, he expressed himself as willing to enter into our plans, offering not only to allow us the temporary use of such papers as we desired, but even undertaking to conduct the necessary formalities of calling a jury and instituting an inquest in such a way as to give us time for the investigations we proposed to make.”

- Turning my attention, therefore, in the direction of Mr. Gryce, I found that person busily engaged in counting his own fingers with a troubled expression upon his countenance, which may or may not have been the result of that arduous employment. But, at my approach, satisfied perhaps that he possessed no more than the requisite number, he dropped his hands and greeted me with a faint smile which was, considering all things, too suggestive to be pleasant.

- “That is a very pleasing belief,” he observed. “I honor you for entertaining it, Mr. Raymond.”

- [paraphrased]

“(You) have a niece whom you ——— one too who seems worthy the love and trust of any other man ca—— so beautiful, so charming is she in face, form, and conversation. But every rose has its thorn and (this) rose is no exception. Lovely as she is, charming (as she is,) tender as she is, she is capable of trampling on one who trusted her heart to him to whom she owes a debt of honor a ——ance.

- “Transitory emotions with some are terrific passions with me. To be sure, they are quiet and concealed ones, coiled serpents that make no stir till aroused; but then, deadly in their spring and relentless in their action.”

- “If you don’t believe me, ask her to her cruel, bewitching face.”

- Gryce: “One should never deliberate upon the causes which have led to the destruction of a rich man without taking into account that most common passion of the human race.” Raymond: “In the end, the motive was the usual one of self-interest.”

- Last line of The Leavenworth Case by Anna Katharine Green, which inspired the last lines of my book: “And leaving them there, with the light of growing hope and confidence on their faces, we went out again into the night, and so into a dream from which I have never waked, though the shine of her dear eyes have been now the load-star of my life for many happy, happy months.”

Quotes from Articles incorporated into A Deed of Dreadful Note

- “Normal people are not so much interested in crime itself as they are in the motive behind the act, or in the person committing it, or in the mystery surrounding it, or in some extraordinary circumstance connected with it. To be interested simply in crime, merely as crime, is either morbid or scientific. Most of us are neither. We are just human; and with us it is the motive which rouses our curiosity. In nine times out of ten the motive can be put down as Selfishness. It takes many forms. It is responsible for those crimes which have money as their object. The young man who cannot wait for some relative to die so that he may inherit property; the people who murder in order to collect life insurance; those who kill in order to rob; all the crimes committed to gain money — theft, embezzlement, forgery — all of these are rooted in selfishness, in greed for one’s own self. So are the crimes people commit to be freed from some obligation or duty which they are too selfish to meet. Men kill their wives, women kill their husbands, because they want liberty to go with someone else. Young men kill the girls they have betrayed, because they want to escape the situation they have brought about. Or a man kills someone who possesses some secret which would disgrace the murderer if it were known. Jealous men, jealous women, kill because they can’t have the love they want. And they kill because they want revenge. It is self, self, self, all the way through. If mothers and fathers would analyze crime as I have, it would be a terrible warning to them not to bring up their children to think that their desires and their feelings are the supreme consideration. Root out Self and you would practically eliminate crime. Even those acts which are committed in sudden passion can be laid to the same fundamental cause — lack of training which makes us tolerant of things contrary to our convenience or liking.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “Of the beautiful women I have known, but few have attained superiority of any kind. In marriage they have frequently made failures; why, I do not know, unless the possession of great loveliness is incompatible with the possession of an equal amount of good judgment.… If one does not train the mind, one neglects an endless storehouse of wealth from which she can hope to produce treasures for her own delectation and that of those about her, long after the fitful bloom upon her handsome sister’s cheek has faded with the roses of departed summer.” — “Is Beauty a Blessing?” by Anna Katharine Green, The Ladies’ Home Journal, Mar 1891

- “I eschew prose. Poetry is my forte; story-telling is not possible to me.” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau” by Mary R. P. Hatch, 1889

- “Not for years did I even dream of attempting a novel, though my mother frequently suggested it. Indeed, I went so far as to say I could not write one, feeling daunted by the number of words I should be forced to write to express what could be suggested so readily in a few lines of verse. But this I remember distinctly, that when the question came up I always qualified my refusal by saying internally, “But if I ever do write a story, it shall be one of intricate and complex plot.””— Anna Katharine Green, quoted in Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, by T. Fisher Unwin, 1895

- “A puzzle which absorbs one must be a relaxation. The puzzle of the plot and the rapid movement of the story should take the reader’s minds somewhere else.” —Anna Katharine Green, “Anna Katharine Green Tells How She Manufactures Her Plots,” Literary Digest

- “The thing which interests us most in human beings is their emotions, especially their hidden emotions. We know a good deal about what they do; but we don’t know much about what they feel. We are always curious to get below the surface and to find out what is actually going on in their hearts.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “I always see the end. I plan my whole story before I put pen to paper, and this is the most fascinating part of the work. Otherwise I could never work each part into its proper place, and obtain a harmonious whole.” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, by T. Fisher Unwin, 1895

- “…a critic once told me, ‘Keep out of the magazines if you can.’ If he had only known how hard I had tried to get into them! The girlish larks we indulged in, the costumes, quaint, ugly and curious, we dressed up in, the walks we took past the glaring brick yards, the outré characters we filched for our stories, the plans we sketched, the hopes we matured…” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau” by Mary R. P. Hatch, 1889

- “The poems are well chosen and give me as you meant they should a good guess at your style and quality of your work: they clearly indicate a good degree attained in power of expression, and the specimens together show the variety and range of the thought. I think one is to be congratulated on every degree of success in this kind, because it opens a new world of resource and to which every experience glad or sad contributes new means and occasion. But it is quite another question whether it is to be made a profession—whether one may dare leave all other things behind, and write…” — Letter from Ralph Waldo Emerson, June 30, 1868

- Inspired a scene: “Mr. Johnson, as it chanced, was a friend of our family, and though a very busy man, he was willing to pass on the story. He came to our house in Brooklyn for that purpose, and in view of the condition of the copy I volunteered to read it to him. So he settled himself comfortably in his chair and I began. He said that if it were very bad I needn’t read it at all, and, though he said it more as a joke than anything else, this filled me with a terror that can be more easily understood than described. After I had read two or three chapters I noticed with alarm that his eyes were closed, and, thinking that possibly he might have fallen asleep through sheer lack of interest, I stopped. There was a pause of perhaps half a minute—then, without opening his eyes he said the one word, “More!” So I went on till midnight or later, when the reading was suspended till next day. After it was all read Mr. Johnson was good enough to give the story his approval. In due time the book came out, and that is how I made my start as a story writer.’” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “Writing Her First Book: How Anna Katherine Green’s ‘The Leavenworth Case’ Came to See the Light,” 1900

- “I write from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.… I am still writing with a good hope in my heart… I have not cut 500 lines.… Last night a thought came to me and I wrote it down in the night.”— Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau” by Mary R. P. Hatch, 1889

- “There is a rather general impression, I think, that men are more interested in this sort of thing than women are, but this is not my experience. And I believe that women are often more keen than men in sensing the solution of these mysteries. Women have more subtle intuitions than men have — a fact which should make them valuable in actual detective work.”— Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “And if, in addition, there is some mystery about the motive, or about the act itself, we follow every detail of the case with what is commonly called ‘morbid curiosity.’ It isn’t morbid. It is perfectly natural and legitimate. These people are like us; or, as I said before, they are what we perhaps only dream of being — rich, cultivated, powerful. That they should commit murder, for instance, seems as strange as that we should ourselves. It is this strangeness that interests us. It is as if a member of our own family should suddenly betray an unexpected and terrible trait; should do something so grotesquely horrible that we cannot reconcile it with what we know of them. Crime must touch our imagination by showing people, like ourselves, but incredibly transformed by some overwhelming motive.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “The other night I had a dream, which has impressed a story on my mind,” she began. “It is so passionate, so strong, so subtle, so dread, dark, and heart-rending, it ought to be written with fire and blood. It will require all my enthusiasm, study and power, and then I may fall short, but I believe I shall try. Perhaps it is somewhat sensational, but I hope by characterization and earnestness to lift it to a higher ground.” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in “An American Gaboriau” by Mary R. P. Hatch, 1889

- “When I was about fourteen I began a story more elaborate than any I had before attempted. The hero was named Leavenworth, but the plot contained nothing which could in any way connect this tale with the one I afterwards published.” — Anna Katharine Green, quoted in Good Reading About Many Books Mostly by Their Authors, by T. Fisher Unwin, 1895

- “The other reason why murder is the most interesting theme for a mystery story is that the act involves two persons. They alone have held the explanation. And one of them has been silenced forever! That lifeless body, with its lips sealed on the great secret, becomes an object of thrilling interest. There is no other crime in which you have that situation. That in itself appeals with tremendous force to your imagination. You feel that you must know what those silent lips would tell if they could only speak. And when, in the story, you come to the actual telling of just how the murder was committed, you read it as if it were being spoken by the dead man himself. Isn’t that true? Haven’t you felt, when reading, perhaps, the account of a mysterious murder: “Oh! if only the dead could speak!” And you try to think, to imagine, what they would have to tell.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “There is another thing about crime which interests an amazing number of people. It helps to account for the fact that so many people read detective stories and follow the newspaper accounts of strange criminal cases. In reading an ordinary novel, they simply let the current of the story flow through their minds. But when they read a detective story, they are all the time figuring on the solution of the mystery, trying to guess how it is coming out. And they do the same thing when they follow a criminal case in the papers.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “I think it is very rare for a murderer to escape detection. No matter how carefully a crime may be planned, or covered up, the criminal almost invariably forgets some significant detail. Curiously enough, Nature herself seems to be in league with circumstances to convict him. She puts a little muddy spot in his path so that he leaves a footprint. Or she blows a curtain aside at the very instant that a passer-by can catch a glimpse of his face. Or she twists the current of a stream so that some evidence of his guilt floats to the surface. Crime is contrary to Nature. And Nature often seems bent on punishing it.” — Anna Katharine Green, “Why Human Beings Are Interested in Crime,” 1919

- “Her “Leavenworth Case” is used in Yale College as a text-book, to show the fallacy of circumstantial evidence, and it is the subject of many comments by famous lawyers, to whom it appeals by its mastery of legal points.” — Woman of the Century, 1893

- Inspired Epilogue: “From that time till a date quote two years later she lived in a little world of her own. She had the plot all mapped out before she began, but it had to be changed and modified as the work progressed, and much of the writing had to be done over and over again. On several occasions she felt sorely tempted to burn the manuscript and forget it. It was not until the story was two thirds written that she dared say anything about it to anyone. Then she showed the copy to her father, who read it, saw that she had struck a vein, and encouraged her to finish the tale, albeit he suggested many modifications. These the daughter accepted without question, for her father was a lawyer, and his suggestions were all along the line of practicality, logical development and conformity to the legal technicalities in the parts which had to do with the courts. ‘I felt grateful to my father for his kindness in helping me,’ says Mrs. Rohlfs when talking of the circumstances now, ‘but I must confess that the way he tore some of my most cherished construction all to pieces was almost disheartening. However, I reconstructed and pieced together the parts which he had condemned, and set about completing my work. ‘I was then eager to take the copy to a publisher, but my father suggested that it ought to be revised again and by a judge. So to a judge of our acquaintance the copy was taken, and he waded through it most patiently. I say this advisedly, for, as it then stood, the manuscript of The Leavenworth Case was the strangest looking mass of paper you ever saw. You see, I had written part of it at home in Brooklyn, part of it at the seashore, part of it in the mountains and other parts wherever I had chanced to be as a guest, on journeys and so on. I had procured my paper and ink from the nearest dealer in every case without a thought to uniformity. Chromatically the copy was more like Joseph’s coat of many colors than anything else I can compare it to, for some of the paper was white, some blue, some pink and some buff. But the judge was very encouraging in his report on the work. It had held his interest from the first to last, he said, and the only criticism that he could offer was on my use in one place of the word ‘equity.’ So far as the word’s ordinary meaning was concerned I had used it properly, but it had a significance in legal parlance which I had failed to grasp. ‘Well I fixed up the word equity and took the much scarred manuscript to the head of a well known publishing house. He didn’t mind the appearance of the copy—though I’ll confess I’d hesitate to offer such manuscript to any one nowadays—and had it read. He warned me, though, that 150,000 words was altogether too long. ‘The reports of the readers were favorable in the main, but the publisher would not regard them as conclusive. “Now,” he said, “you cut out 60,000 words and then get Rossiter Johnson to read it. If he reports favorably we’ll bring out your book.” It had been hard enough work to write the story in the first place, but it was harder still to cut out one-third of what had cost me so much time and effort, but I shut my eyes so to speak and after several days of hard work the excisions were performed.” — “Writing Her First Book,” Kansas City Star, 1900

- “Her father was disappointed that she had given up poetry until he read the first half of her book. Then he agreed she had found her place and became her critic.” — “Anna Katharine Green Tells How She Manufactures Her Plots,” 1918

- “It is related that when “The Leavenworth Case” was published in 1878, the Pennsylvania Legislature turned from politics to discuss the identity of its author. There was the name on the title-page — Anna Katharine Green — as distinct as the city of Harrisburgh itself. But it must be a nom de plume, some protested. A man wrote the story — maybe a man already famous — and signed a woman’s name to it. The story was manifestly beyond a woman’s powers. Feminine names were considerably scarcer in the American fiction list then than they are to-day, when girls fresh from the high school take a place among the authors of the “best-selling” books. A New York lawyer happened to be present at the politicians’ discussion. “You are mistaken,” he said to the incredulous. “I have seen the author of ‘The Leavenworth Case’ and conversed with her, and her name is really Miss Green.” “Then she must have got some man to help her,” retorted the more obstinate theorists. They strongly remind us of the characters whom Miss Green — as we shall call her for the moment — portrays so skillfully, the self-willed characters that aim so well, but do not hit even the target, not to mention the bull’s-eye.” —Little Pilgrimages Among the Women Who Have Written Famous Books, 1901, “ANNA KATHARINE GREEN” by E.F. Harkins and C.H.L. Johnston

Pick Up a Copy of A Deed of Dreadful Note!

A Deed of Dreadful Note, first in the Anna Katharine Green Mysteries, is the first and only historical fiction ever written featuring the Mother of Detective Fiction!

Fifteen years before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle published A Study in Scarlet, Anna Katharine Green began writing The Leavenworth Case, inspiring the creation of detectives like Sherlock, Poirot, and Wimsey, as well as almost every device and convention we now recognize as standard in detective mystery fiction.

When her father’s client is found murdered, Anna takes up the call to prove innocent the young girl accused of the murder. The investigation inspires many of the events, characters, and descriptions that would later be published in her debut novel.

A love letter to mystery and writing itself, A Deed of Dreadful Note is an homage and reintroduction to an author who was the Agatha Christie of her time but a forgotten female today.

This book is a fictionalized account of how Anna Katharine Green’s first novel may have come to be…

NOW AVAILABLE!

Ebook—Amazon (other formats will be available in 3 months)

Audiobook—Wherever audiobooks are sold! Support local and order through Libro.fm!

Print—Order a signed copy from me here! Support local and ask your favorite independent bookstore to order in a copy!

Be sure to request the book through your local library, as well!

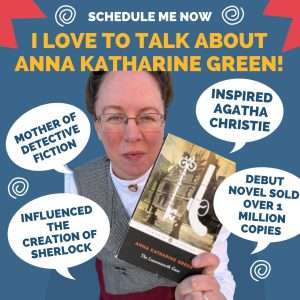

Interested in having me speak about Anna Katharine Green?

If you haven’t noticed already, I love to talk about AKG!

Please email me at author(at)patricia-meredith.com, or DM me on Instagram or Facebook to check my availability near and far! I am available for both in-person or virtual engagements.

—Learn more about Anna Katharine Green—

Watch my YouTube Channel playlist all about Anna Katharine Green.

Head here for a complete timeline of Anna Katharine Green and the History of Mystery Fiction.

AKG and I have a lot in common, it turns out! Watch my video and read this post to learn why I consider Anna Katharine Green my sister from another century.

November 11th is Anna Katharine Green’s birthday! Read this post to learn more about her impact on mystery fiction.

Find my full review, great quotes, and learn how Anna Katharine Green inspired Agatha Christie here from when I re-read The Clocks, and began to really research who this Green woman was.

Read my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read The Leavenworth Case.

Find my full review and great quotes here from the first time I read That Affair Next Door, the first Miss Butterworth case.

—Follow Me Here—

Sign up for my newsletter to be the first to hear all the details! You’ll also receive The Leavenworth Case, complete with my special introduction, for FREE for signing up! (Audiobook read by Andrew D. Meredith coming soon!)

Be sure to also follow me on Instagram and Facebook to hear the latest news concerning new book releases and events. And of course, subscribe to my YouTube channel!

You can also add my books to your Want to Read list on Goodreads! Follow my Author Page while you’re there so you’ll be notified when this new book is updated! You can add A Deed of Dreadful Noteto your Want to Read list here!